Where Are Your Memories Stored?

When I ask this question in my workshops, most people say memories are stored in their brain or in the brain and body (as in muscle memory).

That’s pretty logical i’d say. However its a bit old school…

The most accurate understanding at the moment is that our memories are not stored in the brain or the body, but in some kind of memory field that is beyond the physical body.

The traditional, but now outdated, theory of memory is that when you have an experience via your five senses, bio-chemical and bio-electrical signals leave a trace in the your nervous system and make slight modifications to the neuron circuits in your brain cells, creating a pattern of neuronal connections that represents that memory (memories that go to your long-term memory, instead of your short-term memory, “storage banks” that can be retrieved).

When the same or sufficiently similar stimuli that laid down the original memory are received again, that occurrence activates your brain and nervous system and lights up this memory “trace”—and you remember.

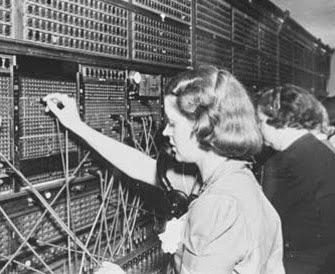

This model suggests that all your memories are held in some physical location in your brain and passed onto your body by the nervous system like some sort of old-fashioned telephone exchange, where the nerve fibres are the wires and the brain is the exchange where the appropriate connections are made.

Many researchers have conducted experiments to amass evidence in support of this theory. There is something to the model, as there do appear to be areas of the brain that store certain, specific memories. Certain diseases or injuries can wipe out access to memories, so there does appear to be a matter-based connection via the brain.

The key here is that access is different from the memories themselves.

We don’t know if losing access to the memory deletes the memory as well. It could be that the memory is still stored in the brain, or perhaps in a field beyond the brain. I say this because experiments show that memory may in fact be a lot more complex than first thought—it may also be a global field phenomenon.

One of the most often cited experiments that belie the ‘memory stored in the brain’ model was conducted by psychologist Karl Lashley, who spent more than thirty years trying to trace the conditioned pathways of the brain to identify the sites of memory storage. Lashley used rats in his study that had been trained to perform specific tasks. He then began systematically removing portions of their brains in an effort to find out when they would lose the memory of those learned tasks and what part of the brain was attached to those memories.

In fact, in studies with both rats and monkeys, Lashley found that he could remove almost the entire brain and still an animal did not lose its ability to remember and perform the tasks. Analogous experiments have shown that even in invertebrates, such as the octopus, specific memory traces cannot be localised. Observations on the survival of learned habits after destruction of various parts of the brain have led to the seemingly paradoxical conclusion that ‘memory is both everywhere and nowhere in particular’.

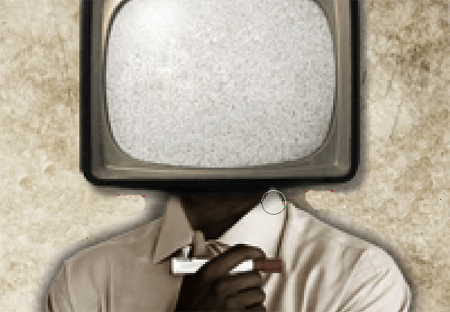

The fact is, there is no direct evidence that memory is stored only in the brain. Thinking that the brain is the home of our memories is the equivalent to thinking that the television set is the home of the sounds and pictures that it plays.

Memory may also be imprinted in some kind of non-body-based information field. We now know that memory is stored in many ways, for instance, as patterns of information in the bio-photon field and other kinds of fields, such as the zero-point field or the Akashic field that hold the memories of everyone and everything and to which we may all have access.

Your brain may not be a memory storage device as much as a tuning device, which like an antenna tunes into the wavelength or frequency of a ‘memory signal’ and directs it into your brain for your use.

The field model of memory has supporting evidence beyond purely biophysical experiments. It appears that when you and other people make new memories—say, for instance, when a host of people across the world all learn a new skill or come to a new understanding—then other people can learn that new skill at a quicker rate. There appears to be some kind of universal memory field, which is an aspect of the global consciousness.

Evidence for this global field dates back to experiments carried out in the 1920’s. You may know of Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov because of the famous ‘Pavolv’s dog’ experiment. But he conducted many other kinds of interesting experiments, including one in which mice were trained to run to a feeding place when an electric bell was rung.

The first generation of mice required an average of 300 trials to learn this skill, but their offspring required only 100 runs to learn it, and their offspring required only 30 trails. The fourth generation learned in only 10 trials.

Somehow each generation of mice inherited information about the skill and so learned more quickly than the generation before it. This inheritance was not based in genetics. Genetics can influence many things, but not learned skills like how to run a particular maze to get food.

Following in Pavlov’s footsteps was Australian researcher W.E Agar and his colleagues, who tested fifty successive generations of mice over a twenty-year period for skill in learning to run and exit a particular maze. The first generation was taught to run a specific maze, and then subsequent generations were introduced to the maze. They found a successive increase in the ease of learning in each subsequent generation. Even more interesting was that Agar’s group also used a control group, where the mice were from a different line in which none had been taught to run this particular maze. Even this line of rats was able to learn more quickly, which suggests some kind of ‘spillover’ effect of the learning.

How can this global learning by association be explained?

One way is via global fields of information.

For example, British biologist Dr. Rupert Sheldrake proposes a theory he calls morphogenesis; morphic fields of information. A morphic field is a sort of energetic and informational template that organizes, shapes, and brings coherence to all things, such that each entity in nature—ants, whales, flowers, rivers, humans—has its particular characteristics because of the information field that shapes it, much like the iron filings are shaped by the magnetic field. In this model, once a pattern or field has been established, then the species that can relate to the field can tune into it by a process called morphic resonance. As new patterns of behaviour and creativity are expressed and imprinted in that morphic field, everything that can relate to that field has access to that information and can use it. In this way, future generations can more easily learn because their ancestors have already laid down the energy and information pattern.

So, your memories and thoughts are not only in your head but imprinted in a global or universal field of information, which your brain tunes into depending on your own “personal energy signature”. The next logical question is, What impact can you have upon these information fields?

Well you are influencing them every second of every day. Your personal energy signature in the form of your beliefs, thoughts and emotions are broadcast outside of your body into these larger energy fields…

More on this next time.